This is a sort-of-review about Limits and Demonstrations, by Jake Elliott and Tamas Kemenczy. It gets just a little spoiler-y, but not in a way that'd seriously compromise your enjoyment.

Most people play chess with pieces and a board, but to many players that's not the actual game -- it's just a mnemonic aid, a thing that keeps track of chesspiece locations so you don't have to remember where your rook is. The people who live and breathe chess, however, can play chess just by reading chess notation in a book, which is to say that the game takes place entirely in their minds. This is more or less what happens when you lose a heated multiplayer match of Starcraft and agonize over what you could've should've didn't do, and wonder what alternate paths you might've taken. Likewise, I'd imagine the most skilled Starcraft players can play Starcraft entirely in their minds.

It's not just in games either: Beethoven was deaf but he could imagine the notes and harmonies so well that it didn't matter, and a Chinese concert pianist was jailed for 6 years but stayed skilled by "practicing in his head."

But I think game designers, designing games directly as a form of conceptual art, is still a relatively new thing.

Zach Gage's Lose/Lose is a shoot-em-up where every enemy is a random file on your computer that will be deleted if shot; it was classified as malware by anti-virus companies, and very few people have actually played it. Probably out of fear of destroying your computer. Vlambeer's GlitchHiker was a game where continued play gradually corrupted the game itself, until the game eventually went "extinct" and died. Jason Rohrer's notorious Chainworld was a special modification of Minecraft, designed to embody a "game as a religion." Prophets were instructed to play it once until they die in-game, then pass it on to someone else to inherit the shared Minecraft world. It existed as a sacred relic on a USB drive, the only copy of the game in the world, and incited controversy when a player wanted to institute a system to monetize it for charity on eBay. (Currently, the USB drive is more or less lost, purchased by an anonymous bidder and hidden away from the world, like any other sacred relic.) Pippin Barr's The Artist is Present is a virtual MoMA simulator that opens and closes at certain times, and you must tediously wait in line for a rare chance to stare into Marina Abramovic's eyes.

You will never play these games, or even when you can play them, these games resist playing.

But, it's important that they existed as games, and that other people have played them or completed them, and we're just as content with never playing these games ever in our lives. There's a bug that allows you to play a pristine uncorrupted instance of GlitchHiker, but at that point -- is that still "GlitchHiker" with a capital G? Chainworld is powerful precisely because its scarcity and context makes it a meaningful metaphor for religion, or a religion in itself. Lose/Lose is powerful precisely because you are afraid of playing it. The Artist is Present is powerful precisely because it's a piece of conceptual art about a piece of conceptual art; real-life museum goers resorted to similar tactics to dodge the long lines, but the vast majority never experienced it.

Now let's talk about Elliott / Kemenczy's new sidestory companion to Kentucky Route Zero, called "Limits and Demonstrations."

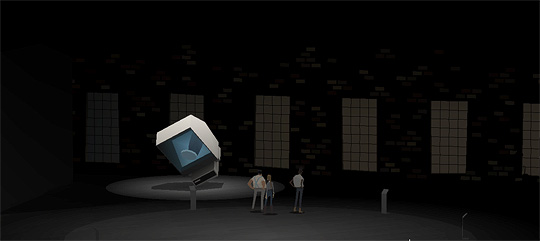

It's extremely fluent in the language of the "new media" art world. Everything sounds like authentic plaque text from some exhibition somewhere, and it's that type of very clever parody where you're not sure if it's actually a parody or if it's earnest about the tone of plaque text. One of the "pieces" is an inside-joke about a discarded, mostly inscrutable, puzzle from Kentucky Route Zero. Another is genuinely breathtaking in motion, and could exist only in a virtual world. There's yet another, pictured above, that's a conceptual "overdub" of Nam June Paik's "Random Access Music."

The developers take great pains to have the characters explain how the installation theoretically works and they even comment on what's interesting about it. You end up imagining the mechanisms in your head. He probably guessed (correctly) that few of his players would know of Paik's real-life piece, assuming they even knew who Paik was, who is more known for his TV sculptures and video art.

So we're left with a game that has to explain how this hypothetical (but real!) art piece would theoretically function and be "interactive" -- except, in this game, this "interactive medium," we don't actually get to perform the interactions that the characters describe! Instead, we interact with the equivalent of an automated phone tree / dialogue menu. That distance is important because it lets you focus on the idea of this hypothetical art piece (cut-up narratives), rather than the actual materiality of this hypothetical art piece (rubbing playback heads on magnetic tape).

And that very idea is what informs the design sensibilities behind Kentucky Route Zero. The lines of tape tell a story about a vast cave, and the visual structure of the tape resembles the web-like structure of both the KRZ overworld / the cave system in the last scene of KRZ.

There's a part in Limits where the characters wonder aloud whether they should "cheat" at the installation, and jump from one side of the tape to another. (Up until then, they had been navigating the tape branches linearly, by walking along them and following the instructions embedded within the tape.) The player is left to choose whether cheating is wrong or whether they "won't tell anyone."

I'd argue most Limits players would choose to cheat. Again, this is the power of distance: it's a game within a game. If the framing game offers us a way to cheat within the "mini-game", then is that still cheating?

Must cheating, in a video game, always involve circumventing the encoded structure of the game, or are there house rules ("roleplay server" / "no rush" / "no AWPs") that must be as inviolable as a players' collision box or the force of gravity?

Does cheating matter if not-cheating results in less enjoyment? Does cheating matter if everyone agrees to cheat? Does cheating matter when most "gamers" will just drop this game in the "art-game" bucket anyway? What is cheating in the context of art?

I don't think I'm projecting these concerns onto Limits: I believe the game, itself, is concerned with these questions and I'm barely extrapolating. It's all there.

If you don't believe me, then you should play it yourself.

But even if you don't ever play it -- then that's okay -- I won't tell anyone.